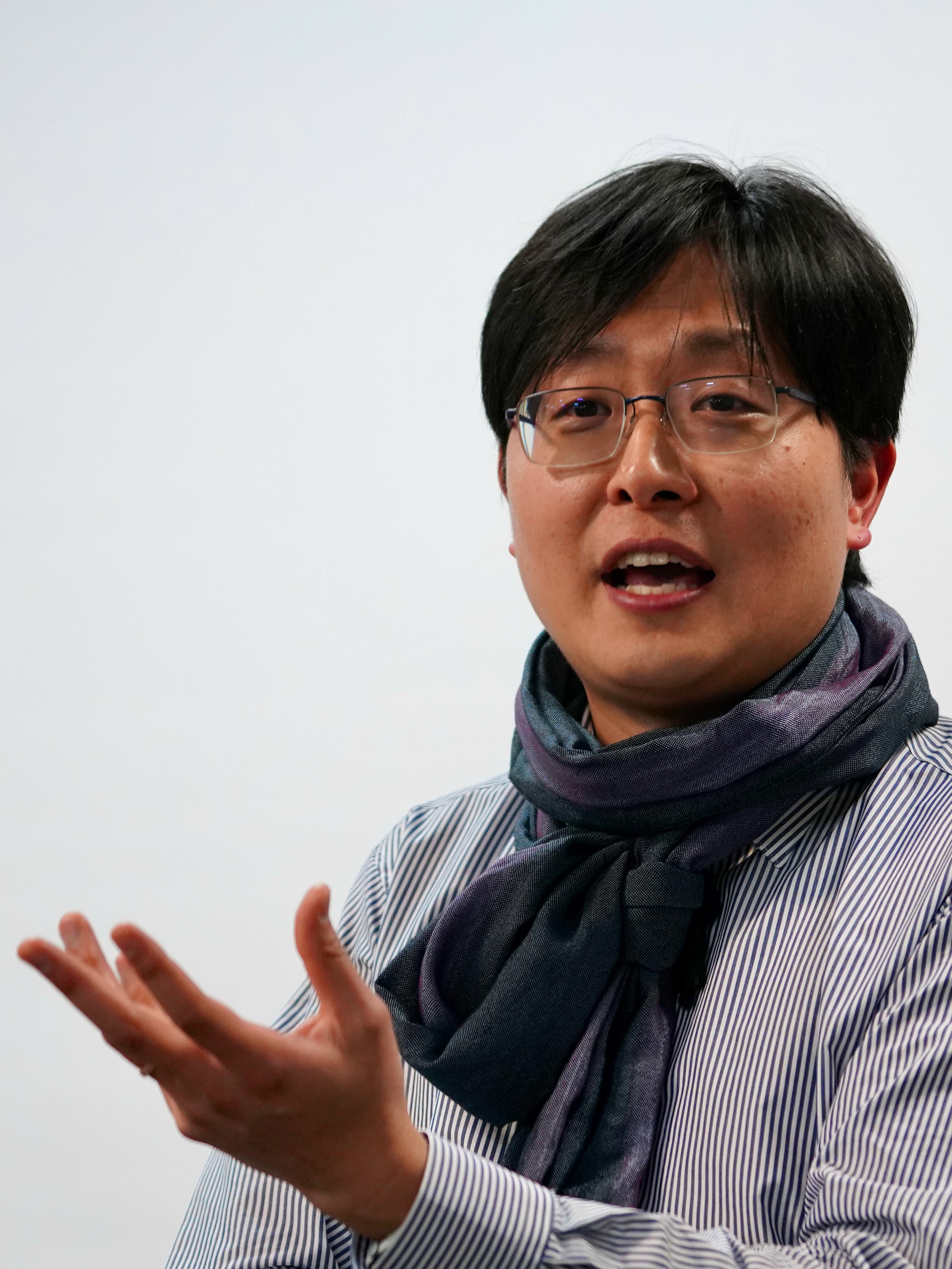

Transnationally Korean:

Diasporic Visions of Kimchi and Nationalism

Kimchi, a fermented vegetable dish popular among Koreans, is increasingly produced, distributed, and consumed outside Korea. For example, industrial production of cabbage kimchi was initiated to supply kimchi to South Korean soldiers and migrant workers overseas. The commercial production and distribution of kimchi in South Korea have expanded along with a rapid increase in the import of made-in-China kimchi. The transnational production and distribution of kimchi in the last few decades do not simply reflect the infiltration of global capitalism into everyday life. They also shape political aspirations and imagination. The South Korean government and media celebrate Made-in-Korea kimchi’s export as an international recognition of its Korean heritage. When the diplomatic conflict between China and South Korea escalated, Chinese consumers boycotted kimchi to show their patriotic commitment. In other words, kimchi is not simply produced through a global economic network; it also produces political sentiments, desires, and imaginations within and across South Korea.

Then, how do nationalist sentiments, discourses, and imagination condition transnational markets and economic interconnections, and vice versa? My book project, Transnationally Korean: Diasporic Visions of Kimchi and Nationalism, explores the coproduction of nationalism and transnational capitalism from a diasporic perspective. As ethnic Koreans in China with bilingual and cultural proficiency, Korean-Chinese entrepreneurs have positioned themselves as transnational mediators, facilitating profitable connections between Korea and China. However, nationalist discourses and patriotic sentiments, which call for solidarity among people in territorial nation-states, jeopardize their diasporic belonging and, more importantly, their business relying on transnational connections between Korea and China. Thus, Korean-Chinese kimchi manufacturers and distributors have carefully monitored nationalist politics across South Korea and China, based on which they readjust business strategies, for example, switching between export and domestic sales, redesigning their product packages, and reformulating the supply chains.

Drawing upon my ethnographic and archival research on the Korean-Chinese kimchi industry, I interpret their business tactics as a diasporic remaking of the distance between “Korea” and “China.” Rather than accommodating nationalist sentiments and aligning their economic and political commitment to Korea or China, Korean-Chinese entrepreneurs innovatively reformulate the distance between Korea and China, using semiotic, aesthetic, and logistic devices to reframe it as a cultural, ethnic, and regional gap their products bridge. In this way, the distance between Korea and China is not simply a given external reality for diasporas to live with; instead, it becomes a means that diasporic entrepreneurs reimagine and repurpose to pursue their economic and political aspirations. Following the diasporic entrepreneurs’ visions and efforts, I explore the possibilities of economic interdependence, political belonging, and cultural exchanges that do not reproduce the discriminative and contentious nationalist politics—the possibility of “Korean” kimchi made and sold by Korean-Chinese.

By analyzing the friction between diasporic connectivity and nationalist belonging in the kimchi industry, my research engages in interdisciplinary discussions on nationalism, global capitalism, and diasporic connections. Drawing upon material culture (Edensor 2002; Foster 2002) and migration studies’ (Skrbis 2017; Thiranagama 2014) approaches to nationalism, the project explores how a commodity’s transnational production, circulation, and consumption reconfigure nationalist orientations and sentiments. Following the transnational trajectories of Korean-Chinese and kimchi, the project critically analyzes how hostile, discriminative, and combative politics—the legacies of colonialism and Cold War imperialism in Northeast Asia (Barlow 2012; Chen 2010; Koga 2016; Schober 2017)—persist, not despite but because of transnational economic relationships. By contextualizing Korean-Chinese political aspirations (Kwon 2023; Kim 2016; Park 2015) embedded in the Korean-Chinese kimchi industry, the project analyzes how the diasporic mode of being is aligned with territorial nationalism and transnational capitalism. Ultimately, my research engages with a classic anthropological question relevant to the current moment: why and how do we become more connected and divided simultaneously (Evans-Pritchard 1940; Mauss 1921; Turner 1957)? By discussing how political friction becomes a condition and production of economic interconnections, I contribute to anthropological theories of sociality, (dis)connections, and (un)boundedness.